by John de Ridder

The popularity of Netflix illustrates how market and technology shifts are posing headaches for carriers. Canada has recently tried to address bandwidth pricing but expect more developments.

In 2007, Netflix started streaming its movie and television catalogue to subscribers in the USA and now has over 23 million customers in place. The same unlimited movie download offering was expanded to Canada in 2010 at a cost of $7.99 a month. By August 2011, the service had signed up 10% of Canada’s broadband households; where signing up the same percentage (albeit more homes) took six years in the United States.

The success of the Netflix offerings is starting to create headaches for carriers and ISPs as they do not get revenue contribution from over-the-top applications like Netflix and yet have to invest to carry the extra traffic. The headaches remain after the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission’s (CRTC’s) recent decisions.

Bandwidth Headaches

Digitisation of broadband networks (both fixed and mobile) is causing tectonic shifts in business models. Traditionally, carriage and content went together: not any more. Entertainment was the ‘killer app’ that spurred the building of cable networks. The builders assumed they would be the providers of the content. But the impetus for delivering content over broadband is now coming from non-traditional sources that do not build the networks they rely on.

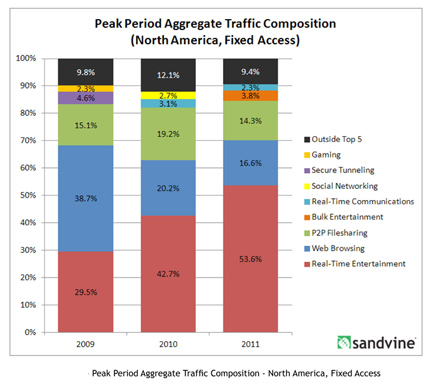

Not only have the builders of networks been deprived of the revenues that they expected out of video, but also have to augment their networks to keep-up with the growth in video traffic; for which they earn very little. Over half the current downstream traffic on fixed networks in North America is accounted for by real time entertainment.

“Intelligent broadband network solutions” provider Sandvine reports that Netflix accounted for 32.7 percent of all North American peak fixed access downstream content in the Fall of 2011. That puts Netflix way beyond the other three top Internet protocols or services by daily volume—approaching double HTTP (17.48 percent), almost three times YouTube (11.32), and nearly four times BitTorrent.

Some carriers’ knee-jerk reaction to the first manifestation of this kind of traffic was to block file-sharing networks like BitTorrent. This was discriminatory and not compatible with net neutrality.

The obvious neutral solution is to charge per GB irrespective of the content or its source. Volume based charging goes against the grain for those accustomed to unlimited downloads on broadband. And it is bad news for Netflix at about 2GB per hour (double with high definition) and average usage around 40GB per month. Twenty Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries have no data caps at all among their broadband offers. But things are changing. Most Netflix customers are in the USA and in May 2011, AT&T slapped 150Gb and 250GB data caps on its DSL and U-Verse customers. This remedy has been over-turned in Canada.

Canada

In 2000 the CRTC permitted cable carriers to introduce usage caps and/or usage-based billing (UBB) charges for their wholesale services if UBB was also applied for their retail customers. Later, this option was extended to telephone companies offering broadband access.

On 25 January 2011 (Decision 2011-44), the Commission set the UBB rates at retail minus 15 percent. But the concession was not enough for many independent ISPs which together account for just 6 percent of the residential retail market. They hoped the CRTC would set a 50% discount. The January decision ignited consumer backlash and created a wave of public scorn that hit Ottawa ahead of the May federal election, quickly turning into a hot-button issue for a minority Conservative government and opposition parties alike. Also Netflix Inc. expressed serious concerns about its future in Canada – “[usage-based billing] is something we’re definitely worried about,” (Reed Hastings, chief executive of Netflix). On February 3, 2011, the federal Cabinet advised the CRTC that if it did not review the decision and come back with a new one, it would be reversed.

What does this mean going forward for bandwidth pricing?

The revised model that the CRTC finally produced on November 15, 2011 offers two options. First, for companies that proposed a usage-based model, their tariffs have to be based on the approved capacity model, effective February 1, 2012. For companies that proposed a flat rate model, their tariffs were approved effective immediately.

The capacity model requires ISPs to choose what bandwidth of pipe it wants in order to carry traffic between aggregation points (e.g. street cabinets) and the handover point. This is similar to the wholesale model proposed for the new broadband network in Australia. If ISPs do not order enough capacity, their traffic will become congested without affecting other ISPs.

This should appease Netflix and others but where is the incentive for ISPs to buy bigger pipes to accommodate traffic for which they get little or nothing? The bandwidth headache will remain until get to linear pricing on volumes. Data caps are just the first step towards that.

Sources:

CRTC Telecom Regulatory Policy CRTC 2011-703 [15 Nov 2011] http://www.crtc.gc.ca/eng/com100/2011/r111115.htm

Financial Post , 1 October 2011 http://www.nationalpost.com/news/Netflix+face+Canadian+regulations/5487301/story.html

Financial Post, 16 November 2011 http://www.financialpost.com/news/CRTC+ruling+hits+smaller+ISPs/5716827/story.html

OECD Communications Outlook, 2011

Sandvine, Global Internet Phenomena Report, Fall 2011 http://www.sandvine.com/news/global_broadband_trends.asp