November 2011 Bandwidth: Netflix, EU Broadband, and the Understanding Divide

By John de Ridder

The popularity of Netflix illustrates how market and technology shifts are posing headaches for carriers. Canada has recently tried to address bandwidth pricing but expect more developments.

In 2007, Netflix started streaming its movie and television catalogue to subscribers in the USA and now has over 23 million customers in place. The same unlimited movie download offering was expanded to Canada in 2010 at a cost of $7.99 a month. By August 2011, the service had signed up 10% of Canada’s broadband households; where signing up the same percentage (albeit more homes) took six years in the United States.

The success of the Netflix offerings is starting to create headaches for carriers and ISPs as they do not get revenue contribution from over-the-top applications like Netflix and yet have to invest to carry the extra traffic. The headaches remain after the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission’s (CRTC’s) recent decisions.

Bandwidth Headaches

Digitization of broadband networks (both fixed and mobile) is causing tectonic shifts in business models. Traditionally, carriage and content went together: not any more. Entertainment was the ‘killer app’ that spurred the building of cable networks. The builders assumed they would be the providers of the content. But the impetus for delivering content over broadband is now coming from non-traditional sources that do not build the networks they rely on.

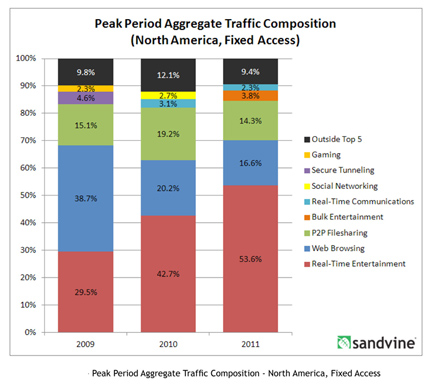

Not only have the builders of networks been deprived of the revenues that they expected out of video, but also have to augment their networks to keep-up with the growth in video traffic; for which they earn very little. Over half the current downstream traffic on fixed networks in North America is accounted for by real time entertainment.

“Intelligent broadband network solutions” provider Sandvine reports that Netflix accounted for 32.7 percent of all North American peak fixed access downstream content in the Fall of 2011. That puts Netflix way beyond the other three top Internet protocols or services by daily volume—approaching double HTTP (17.48 percent), almost three times YouTube (11.32), and nearly four times BitTorrent.

Some carriers’ knee-jerk reaction to the first manifestation of this kind of traffic was to block file-sharing networks like BitTorrent. This was discriminatory and not compatible with net neutrality.

The obvious neutral solution is to charge per GB irrespective of the content or its source. Volume based charging goes against the grain for those accustomed to unlimited downloads on broadband. And it is bad news for Netflix at about 2GB per hour (double with high definition) and average usage around 40GB per month. Twenty Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries have no data caps at all among their broadband offers. But things are changing. Most Netflix customers are in the USA and in May 2011, AT&T slapped 150Gb and 250GB data caps on its DSL and U-Verse customers. This remedy has been over-turned in Canada.

Canada

In 2000 the CRTC permitted cable carriers to introduce usage caps and/or usage-based billing (UBB) charges for their wholesale services if UBB was also applied for their retail customers. Later, this option was extended to telephone companies offering broadband access.

On 25 January 2011 (Decision 2011-44), the Commission set the UBB rates at retail minus 15 percent. But the concession was not enough for many independent ISPs which together account for just 6 percent of the residential retail market. They hoped the CRTC would set a 50% discount. The January decision ignited consumer backlash and created a wave of public scorn that hit Ottawa ahead of the May federal election, quickly turning into a hot-button issue for a minority Conservative government and opposition parties alike. Also Netflix Inc. expressed serious concerns about its future in Canada – “[usage-based billing] is something we’re definitely worried about,” (Reed Hastings, chief executive of Netflix). On February 3, 2011, the federal Cabinet advised the CRTC that if it did not review the decision and come back with a new one, it would be reversed.

What does this mean going forward for bandwidth pricing?

The revised model that the CRTC finally produced on November 15, 2011 offers two options. First, for companies that proposed a usage-based model, their tariffs have to be based on the approved capacity model, effective February 1, 2012. For companies that proposed a flat rate model, their tariffs were approved effective immediately.

The capacity model requires ISPs to choose what bandwidth of pipe it wants in order to carry traffic between aggregation points (e.g. street cabinets) and the handover point. This is similar to the wholesale model proposed for the new broadband network in Australia. If ISPs do not order enough capacity, their traffic will become congested without affecting other ISPs.

This should appease Netflix and others but where is the incentive for ISPs to buy bigger pipes to accommodate traffic for which they get little or nothing? The bandwidth headache will remain until get to linear pricing on volumes. Data caps are just the first step towards that.

Sources:

CRTC Telecom Regulatory Policy CRTC 2011-703 [15 Nov 2011] http://www.crtc.gc.ca/eng/com100/2011/r111115.htm

Financial Post , 1 October 2011 http://www.nationalpost.com/news/Netflix+face+Canadian+regulations/5487301/story.html

Financial Post, 16 November 2011 http://www.financialpost.com/news/CRTC+ruling+hits+smaller+ISPs/5716827/story.html

OECD Communications Outlook, 2011

Sandvine, Global Internet Phenomena Report, Fall 2011 http://www.sandvine.com/news/global_broadband_trends.asp

Competition and Broadband in the EU

by Joanna Taylor

In Europe there is a healthy competitive market for the telecommunication services, including broadband services, to end users. What is the basis for this competition? The fundamental attributes are explored briefly below. Could they be transferred to the western side of the Atlantic? There seems to be no reason why not!

Economists and lawyers generally agree, to the extent that they agree upon anything, that healthy competition is a “good thing.” Competition drives down prices and encourages innovation while its opposite state, a monopoly creates an environment where innovation is limited and there is no market pressure driving down prices. In essence, an open, competitive market provides a higher degree of public good than a monopolistic, closed market focused on exploiting its market dominance to maintain high prices or restrict investment.

Economists and lawyers generally agree, to the extent that they agree upon anything, that healthy competition is a “good thing.” Competition drives down prices and encourages innovation while its opposite state, a monopoly creates an environment where innovation is limited and there is no market pressure driving down prices. In essence, an open, competitive market provides a higher degree of public good than a monopolistic, closed market focused on exploiting its market dominance to maintain high prices or restrict investment.

Economists and lawyers often refer to “natural monopolies,” as those that result from a set of circumstances where only one supplier is likely to enter the marketplace. It is argued that these conditions are present in the telecommunications access market. For example, when the final section of a wired (fixed line or last mile) service closest to a house or business premises is dedicated to the individual customer, and most customers only have the opportunity to purchase service from a select provider, there is very limited opportunity for a second provider to invest profitably in a duplicate access network. This is equally true in the broadband and mobile/wireless contexts and on both side of the Atlantic ocean.

Typically the incumbent, or first operator, will have created a largely universal copper network, and indeed has sometimes had an obligation to do so. In comparison, a new market entrant in its start-up phase would typically not be able to afford to re-create such a network in its entirety and will need the capability to link to the other network to provide the services they are marketing to potential customers. Typically, the service package includes the customer’s ability for their customer’s calls to connect with their competitor’s customers. However, if a new entrant’s network is unable to deliver calls made by its customers to people or organizations that procure services from another provider the new entrant will fail. In contrast, the profit maximising position for a monopoly network operator would be to refuse to deliver calls that originate from another network, or charge extortionate amounts to do so.

If market entry is to be encouraged, some form of regulation is required to force provider interconnection and control its prices.

In Europe, these twin concepts of the benefits of competition and the natural monopoly of the access market have long been recognized as appropriate solutions to sustainable competition and new market entry. Two recent public consultations on the regulatory regime have focussed on how to increase effective operation without any perceived need to discuss if the fundamentals require changing.

The European regulation that supports this service level competition is based on European competition law. The key difference is, however, that the regulation restricts behaviours in advance, ex-ante rather than ex-post, to prevent potential exploitation by operators of monopoly or quasi monopoly positions. As noted above, exploitative monopolistic behaviours may take the form of excessive pricing or market foreclosure, and the rules operate to counter both.

In brief, the system is as follows:

- The regulator has an obligation to review the telecommunication markets every few years and assess if any operator has significant market power (SMP), broadly equivalent to 40% market share, that would enable it to act anti-competitively,

- If an operator is found to have SMP, it can be required to offer wholesale services to other operators that enable them to compete on the retail market,

- These wholesale services should typically be offered on a non discriminatory basis to all other operators, and the retail arm of the operator with SMP should consume those same services when delivering services to its end customers, and

- The prices for the wholesale services should be cost orientated, and there should be sufficient margin between the wholesale and retail prices to cover the costs of retailing.

Over time the number of SMP markets has tended to fall, as competition has developed and entrants have built their own networks. A market entrant will initially invest in a core network, and as its customer base grows, it builds its network out towards the edge of the network, concentrating on the areas of highest customer density and value as this is where the opportunities are greatest . Former TV Cable operators may compete with the ex-incumbent in urban areas but SMP may remain with one, or both operators. The degree of competition in the access network remains limited outside city centres.

This European regulatory standards body is not without its critics, and its implementation, which varies somewhat country by country, could be improved but there is no doubt that the new regulatory standards have created an explosion of service level competition. Not only have consumers and businesses seen significant benefit, but also significant price reductions have been seen in the retail fixed and mobile markets.. Broadband services have got faster without price increases. In the European Union there are over 250 million internet users, with 95% of the population having fixed broadband access available to them, and virtually every European owns a mobile phone .

The regime has not restricted investment in infrastructure, as the roll out of fibre networks into high-density areas demonstrates. A proposal from Germany to exclude fibre networks from the rules was firmly rejected by the European Court of Justice in 2009.

The target for basic broadband for the 100% of the European Community by 2013 and 30mbits by 2020 is being made within this framework, and any development that uses pubic funds for network development is captured.

What would North America look like if this model were adopted? There is interconnection and the FCC requires some services to be offered on a wholesale level, but the whole process is shrouded in complexity. A general obligation for local access providers to provide wholesale services and to consume them themselves in a transparent and non-discriminatory manner might be just the catalyst the market needs!

How easy would a move to this model be? Well, that depends on the hearts and minds of those involved. The European model does not prevent operators being successful or prevent those who are inefficient from failing. The most successful are those that understand the logic of the competitive model and embrace it, whether as incumbent or entrant. Perhaps now is the time that this approach should be considered?

Quick Bytes

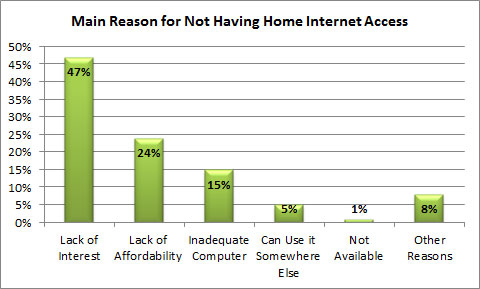

The U.S. Department of Commerce recently released a report entitled “Exploring the Digital Nation – Computer and Internet Use at Home – a long report with several important findings. But our favorite happens to be results showing why the 32% of American homes without home Internet access don’t subscribe to a service.

So there are more than 34 million households in the U.S. without Internet access… and while we’ve been quick to blame the digital divide, the price, that does not seem to be the main challenge. Even if we combine the numbers for Affordability (24%) and Inadequate Computer (15%), it still comes in below the number one reason: Lack of Interest. So while affordable, pervasive availability is critical – it is just as important (if not moreso as the study suggests) to show the “So What” of broadband… WHY should people adopt and then utilize broadband and its e-solutions?So while the digital divide is real and significant – perhaps as broadband evangelists, we should focus just as much effort on the the “understanding” divide.

So there are more than 34 million households in the U.S. without Internet access… and while we’ve been quick to blame the digital divide, the price, that does not seem to be the main challenge. Even if we combine the numbers for Affordability (24%) and Inadequate Computer (15%), it still comes in below the number one reason: Lack of Interest. So while affordable, pervasive availability is critical – it is just as important (if not moreso as the study suggests) to show the “So What” of broadband… WHY should people adopt and then utilize broadband and its e-solutions?So while the digital divide is real and significant – perhaps as broadband evangelists, we should focus just as much effort on the the “understanding” divide.

The Move to Internet Enabled Jobs

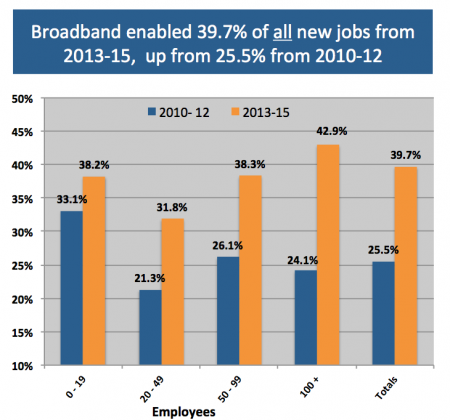

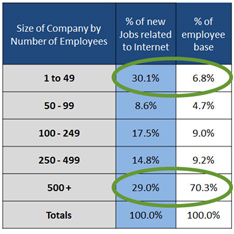

There is job creation and loss in any economy – the question is whether more jobs are being created than lost. And whether the jobs lost can be overcome with new jobs created. SNG research in two US States reveal that up to 30% of the new jobs being created for small businesses (1-49 employees) and large firms (over 500 employees) are directly related to the Internet.

Our research also shows that small businesses create ten times (10x) more jobs related to the Internet as compared to large firms based on total employment. This is significant because if you’re looking to help create jobs in your region, it’s small businesses that are your biggest lever for local economic development.

Our research also shows that small businesses create ten times (10x) more jobs related to the Internet as compared to large firms based on total employment. This is significant because if you’re looking to help create jobs in your region, it’s small businesses that are your biggest lever for local economic development.

Also, given how much of new job creation is related to the Internet – broadband is becoming increasingly important for local economic development. Which means that without high quality, reliable and affordable bandwidth, it becomes increasingly challenging for firms of any size to stay competitive in an economy where more and more business activity and collaboration is online.